An Incomplete Maintainer’s Guide to the Best of Pro Wrestling 2020 Q4

Every month I keep a document running in which I write about the wrestling matches I watch. Once upon a time I felt the need to jot down every match I enjoyed, and to quantify how much I enjoyed it. As time goes by I find myself more and more willing to let go of matches that are just “good”. The flip side of this is an increasing tendency to write paragraphs upon paragraphs about a much smaller selection of matches. Often these matches seem worthy of this kind of analysis because they raise some interesting set of questions about the art of wrestling, either by fucking with the form or by absolutely nailing some specific aspect of it. Here, then, is nothing more and nothing less than a round-up of the matches from the last three months of 2020 which moved my pen the most.

To subscribe to my Luke’s monthly match review newsletter and access other content besides, including a series of articles rounding up the best that wrestling in 2020 had to offer, visit https://oystersearrings.substack.com/

Takumi Iroha, Rin Kadokura & Maria vs. Mio Momono, Mikoto Shindo & Mei Hoshizuki

1 October, Women’s Wrestling ASSEMBLE 1, Ueno Park Mizudori

It was the luck of the draw that put Marvelous in this main event slot ahead of all the other promotions but my how they proved their worth. Marvelous proved in the 15 minutes they were given here that they’re ready to take over the wrestling world if only they can keep their roster fit and healthy (I write this on the day Takumi reportedly sustained a serious-looking knee injury in a match at Shinkiba 1st Ring) and find the right kind of outlet for their stuff. There was some speculation on Twitter after Mio pinned Takumi here that Nagayo had made the decision to use the big finish they’ve been keeping in their back pocket for several years now – Mio reversing the Splash Mountain into a Yoshi Tonic to get the first big win over her mentor – after realising they’d managed to bag the headline slot of this historic show. But regardless of whether this is true or not, what this match showed beyond any doubt is that all six of these performers have a special gift which allows them to connect with audiences like few other wrestlers of their generation. This was a showcase match which restored some hope for the future of a scene which feels very uncertain right now, but which didn’t for the 15 minutes in which the match was taking place.

Yoshiko & Hiroyo Matsumoto vs. Best Friends (Arisa Nakajima & Tsukasa Fujimoto)

3 October, SEAdLINNNG, Yokohama Radiant Hall

After watching this match I joked on Twitter about how my analysis of “this started off fairly slow but got crazy down the finishing stretch” made me sound like one of those New Japan fans who tries to justify Okada dicking about adjusting his waistband for the first 20 minutes of a match by pointing to the 10 minutes of Rainmaker reversals he did to build to the finish. But I want to stand by that analysis, because here we have a match in which the relatively stately pace of the first half establishes a foundation for the match, namely that these two teams are extremely hard to beat, and creates obvious stakes – the longer these two go back and forth the clearer it becomes that the match is going to be decided by some extra something, by some “moment of magic” as a football commentator would say, and the closer we get to the time limit the more likely we are to get one of those moments, because in those urgent last few minutes there’s also more likely to be some mistake which creates an opening, a pocket of one or two seconds to seize and turn to your advantage. That’s how these sorts of matches should always work, but they don’t, because these four are just uncommonly skilled at big match wrestling in general and tag team wrestling in particular, and this was a complete triumph of big match tag team wrestling.

Mei Suruga vs. Ryo Mizunami

4 October, Choco Pro, Ichigaya Chocolate Square

Roughly a week before I watched this, I watched the Raven vs Rhyno Hardcore Championship match from WWE Backlash 2001 with friends on our weekly Watch2gether stream, and we spoke about the importance that garbage wrestling held in our respective early fandoms. It seems counter-intuitive that a style which revolves around disrupting standard match formulas, introducing foreign objects and outside locations and unheralded scenarios (Crash Holly fighting off Mosh and Thrasher in a children’s play area) would have such a universal impact on the brains of young fans that aren’t evidently even all that jaded with those standard match formulas to begin with, but there it is – there’s something undeniable about maximalist garbage wrestling when it’s done well, whether it’s happening in Attitude Era WWF or in Gatoh Move in 2020.

I’m not jaded with Choco Pro’s go-to match formulas either, but just as in 2001 there was still massive value in the way that Mei Suruga and Ryo Mizunami used the Falls Count Anywhere stipulation to expand on the standard repertoire here, introducing us to two new spaces around Ichigaya Chocolate Square, weaponising a variety of objects we haven’t seen before but which fit neatly into Gatoh Move canon (Emi Sakura’s Queen posters, Mei’s bicycle), and even turning the very notion of pinfalls literally on its head (if Falls Count Anywhere then why not against a wall or an upturned traffic cone, or under a mechanical door shutter?). The Choco Pro crew have been experimenting with the same small core roster in the same tiny room for over 50 shows now, and keep finding ways to be innovative and progressive while working within those limitations. Even so, this match, which finally led us out of that tiny room and unlocked new arenas before our eyes, felt like some kind of unimaginable bounty.

LUMINOUS (Miyuki Takase & Haruka Umesaki) vs. Tae Honma & Maika Ozaki

11 Octobe, DIANA, Korakuen Hall

There were two strands to my enjoyment of this. First, Tae and Takase are pretty much perfect dance partners, I always relish any opportunity they get to do matwork together, and I look forward to the moment Tae finally gets one over on Takase, since she seems to come up short in every meeting they have to date. Second, Haruka Umesaki’s 2020 is perhaps second only to Suzu’s in terms of her rise up the pecking order (this is clearly the story behind their ICE x Infinity Championship match at Korakuen Hall, which is one day away at time of writing), and this match painted in vivid detail the skill-set which she has inherited from her mentor Sareee – here, with Maika and Takase providing periodic punctuation marks, the final act of the match was given over to a battle between Tae and Haruka, in which Haruka managed to withstand Tae’s submissions and stay in the game just long enough to carve out a few tiny openings, chinks in her more powerful opponent’s armour which she then managed, with no small amount of technical virtuosity, to carve out into a more significant advantage and then a well-crafted roll-up for the three. If this isn’t a refracted image of Sareee in her battles with Chihiro Hashimoto from last year then I don’t know what is.

Suzu Suzuki & Ibuki Hoshi vs. Tsukasa Fujimoto & Yuuki Mashiro

17 October, Ice Ribbon, Ice Ribbon Dojo

Every year in joshi wrestling some rookie debuts and completely wins me over by employing tactics right out of left field – last year it was Lulu Pencil, the year before that it was Mei Suruga, and so on. This year’s leftfield rookie of note is Yuuki Mashiro, who has so far 1) challenged Maya Yukihi to a title match at Yokohama Buntai before she’d so much as made her professional debut 2) introduced a jazzy little trademark pose which she insists on going up to the top turnbuckle to strike, even before she’s grown comfortable doing moves from there 3) challenged Suzu Suzuki for the title in the first match after her professional debut 4) introduced a comedic bit that revolves around insisting on having a water break before the match has really got going 5) taken a break to rest and recuperate from some health issues during which time she bit off way more than she could chew in offering to single-handedly produce hundreds upon hundreds of tin badges to be sold off as Ice Ribbon merchandise in live streamed gacha pull sessions, and 6) returned to the ring now proclaiming herself the “Gacha King”, carrying a homemade belt constructed from cardboard and pin badges, and bringing a gacha machine to ringside to be used in all of her post-match promos (of which there is at least one in every match she’s involved with). In the promo segment which followed this match, she had her victorious opponents pull gacha capsules in which were folded hand-written contracts entitling the bearers to one (1) title shot for the Gacha King Championship (this is not the only time she has tried to put her unofficial title on the line against much more experienced opposition).

A day later, in Osaka, Yuuki, who wasn’t scheduled to compete that day, would challenge Tsukka to a singles match immediately after she’d just got done with a hard-fought tag match against the winner’s of this year’s Kizuna Tournament, fully admitting that she was challenging right now because Tsukka was already tired out and she might therefore have a better chance of beating her. Across other shows in October she also attempted to subordinate Rina Yamashita and Satsuki Totoro to her pro wrestling parallel universe, naming them “Gacha King of Osaka” and “Gacha King Tag Team Champion” respectively, complete with more hand-made belts. It’s this kind of blithe overconfidence and lack of social scruples that makes Yuuki an obvious heir to previous leftfield rookies du jour like Maki Itoh and Mio Momono, and I think I’ve finally figured out why I’m so drawn to characters like this – it’s that their ability to override social niceties and not worry about trying to run before they can walk feels enormously liberating for somebody who over-analyses every little decision and interaction to the extent that I do.

Tokiko Kirihara vs. Cherry

18 October, Choco Pro, Ichigaya Chocolate Square

The pivot to daily YouTube uploads last Spring and the past seven months of Choco Pro have altered the picture to such an extent that it’s hard to think back to precisely what Gatoh Move’s appeal was back when their matches were still difficult to access, but this match provided a welcome reminder of the first thing that really blew me away about this organisation – their ability to put together matches which seamlessly blend character comedy (and off-the-wall storytelling) with the kind of technical mat masterclasses that conventional wisdom would hold to be the exclusive preserve of Boring Boys Wearing Black Trunks. This match started out with a Bit where Kirihara, who idolises Cherry, is wearing Cherry’s t-shirt, and Cherry acts all flattered about it before sneakily rolling Kirihara up into a kneebar, and it ended with an extended stretch of gripping shoot-style grappling. There was no need to signal the shift from the “fun” section into the “technical” section, and the story that came through was consistent from bell to bell – “never meet your heroes”, as Akki put it on commentary. A throwback to the sort of thing that used to be more common in Gatoh Move when Masa Takanashi was active there, and up there with his match against Mei last year, which is a very big compliment indeed.

Risa Sera vs. Takayuki Ueki, Itsuki Aoki, Suzu Suzuki, Toshiyuki Sakuda, Hiragi Kurumi, Orca Uto, Akane Fujita, Minoru Fujita, Takashi Sasaki & Yuko Miyamoto

24 October, Risa Sera Produce, Yokohama Radiant Hall

The narrative I have put together in my head of Risa Sera’s career since I started watching Ice Ribbon goes – boring Ace, busts out with deathmatches every now and then but the company isn’t really in favour of running them; gets increasingly fixated on deathmatches to the point she can’t really get motivated to do anything else; eventually begins getting her deathmatch fix outside the company and finds a new balance and drive which once again propels her to the top of the Ice Ribbon title picture for that great Buntai main event with Maya Yukihi; a year later is given a new lease of life by her capture of the FantastICE Championship, which basically amounts to an acceptance on the part of the company brass that deathmatches can now be a feature of the Ice Ribbon universe.

I don’t think this is a water-tight retelling of the story of Sera’s career, but, regardless – this match felt like an arrival point, the first of her three hour-long deathmatch gauntlets to date which was contested for a title (at least technically – in a gesture that only gets more staggering in retrospect, Sera announced at the beginning of the gauntlet that while nobody could capture the FantastICE title off her in this match, if she couldn’t make it to the end of the sixty minutes she would forfeit her claim to the belt). In a similar vein to her match against Rina Yamashita at the Buntai, this raising of stakes made for a match which was arguably more intense than any of the deathmatch spectacles Sera has produced before this one. Here, Sera is not only representing her own interests and desires but this new corner of the wider company which she has been entrusted with stewardship over, and a hardcore style which we know was the principal inspiration for the current top champion and figurehead of the company, Suzu Suzuki. Suzu in fact got her first brief runout in a hardcore match environment here and made the absolute most of it, flinging chairs about with reckless abandon and taking a horrid bump onto a ladder. You sense she’ll insist on more down the line.

It’s not just the shifting of organisational sands and the raising of stakes that made this such a worthy successor to Sera’s previous deathmatch gauntlets – there’s also a sense in which she’s got better over time at executing these kinds of matches and, crucially, at pacing them. There was a moment a little over halfway through where this match started to sag, with Sera’s visible exhaustion leading to some obviously blown spots in the portion of the match where she was in the ring with Minoru Fujita. By the time the final contest with Yuko Miyamoto rolled around, however, Sera had ridden it out and got her second wind and the energy that both she and Miyamoto brought to these closing stages was absolutely electric, with Sera in particular doing everything needed to hammer home the levels of strength and courage needed to pull something like this off. There’s a little over a year left before Sera retires on her thirtieth birthday, and here she made absolutely certain that she’ll be remembered as an Ice Ribbon legend for as long as people continue to talk about that promotion. But I still came away from this wanting more – Risa Sera as Pop Culture icon.

Halloween Battle Royal

28 October , Choco Pro, Ichigaya Chocolate Square

There’s an American comedian called Phil Hendrie who at various points over the past few years has been in the habit of putting out a daily podcast, modelled on a talk radio broadcast, in which he plays all of the characters – improvising the script, taking “calls” from listeners and regular contributors, and representing five different characters in the studio alone. Every so often, as a one-off special, he’ll do something called “The Margaret Gray Players” – Margaret Gray is one of these studio characters – in which he voices characters from the show voicing other characters from the show, usually adapting a famous script like Dickens’ Christmas Carol for the purpose. The in-canon universe of Hendrie’s shows is weird enough, but these off-piste episodes feel carnivalesque in their addition of this extra level of meta-weirdness to proceedings.

Hallowe’en is usually a good time for carnivalesque-feeling hows in the world of joshi wrestling, but often – or at least in the case of Stardom’s annual Mask Fiesta shows – it’s a case of turning a broadly non-wacky enterprise wacky for one special night. Choco Pro shows are already pretty wacky to begin with, so here the carnivalesque spirit absolute overflowed, and there was a general vibe to this match – which won’t be to everyone’s tastes, I’ll admit – of a special one-off production storyboarded and choreographed by kooky theatre kids who live for this shit. Chie threw herself into the role of “sushi shrimp” like it was the part she was born to play. There was also a sense in which every bit of presentational trickery devised by the Choco Pro crew thus far set them in better stead to pull off a novelty match like this than any other organisation; most notably, the way they used a variety of camera techniques when introducing new characters to the fray – panning from left to right to reveal Chie, having Lulu emerge from the bottom of a static frame – is nothing we’ve not seen before in these broadcasts, but that nous and experience they’ve developed in these matters really brought this show to life.

November

Hikari Noa vs. Yuki Kamifuku

7 November, Tokyo Joshi Pro, Tokyo Dome City Hall

The semi-final between Hikari and Mirai Maiumi that took place earlier in the night may have been the better match of the three tournament bouts featured on this card, but I don’t have a ton to say about it – it was a gripping, technically impressive showcase from two continually-rising talents that I’ve been backing for great things since day one; go and watch it now if you haven’t already. This final, however, I do have things to say about. Despite the fact that Hikari and Kamiyu both came into this International Princess title decider at similar levels of status – neither has held a belt before at any level, or experienced much in the way of tournament success in either tag or singles competition – there was a distinct feeling that Hikari felt herself the overdog. We’ve known for a while now that Kamiyu can go, but she still carries an aura of unseriousness with her from the time when she used to come out wearing a little cowboy hat – and she still comes out to a Kids Bop version of Old Macdonald Had a Farm. In the run up to this show, Kamiyu lost her two unit partners, not before losing to one of them in her last big singles match for the promotion (see August’s newsletter for my glowing review of that match against Mina Shirakawa). Hikari won her singles match on that same show – against Raku, but still. Hikari has been knocking at the door of the Tokyo Joshi elite tier even before her Up Up Girls partner Miu Watanabe ascended roughly a year ago. She came into this tournament as clear second favourite, and with Shoko Nakajima dispatched in the semis looked to have all the momentum coming into this final – look at the way she offers Kamiyu a test of strength in the early going, with a full-body expression that says this match is hers to lose.

But of course, Shoko didn’t just dispatch herself – it was Kamiyu that beat her, fairly handily all told, and she did it by just being incredibly difficult to wrestle. Her lanky frame makes her awkward to fold up into submissions or suplexes, and her reach on offence gives her a clear advantage over smaller opponents. Her dropkick, big boots and Famouser – which won her both matches in this tournament – all looked nastier here than at any point before, and even though I’d hoped this show would be Hikari’s coronation, there was something altogether undeniable about the way Kamiyu forced her way through the pack. This wasn’t necessarily a fairytale of a joke wrestler come good, it was a story of a performer who’s been slowly improving her game for years finally finding her feet despite everyone constantly underestimating her. Good for her.

Yuka Sakazaki vs. Mizuki

7 November, Tokyo Joshi Pro, Tokyo Dome City Hall

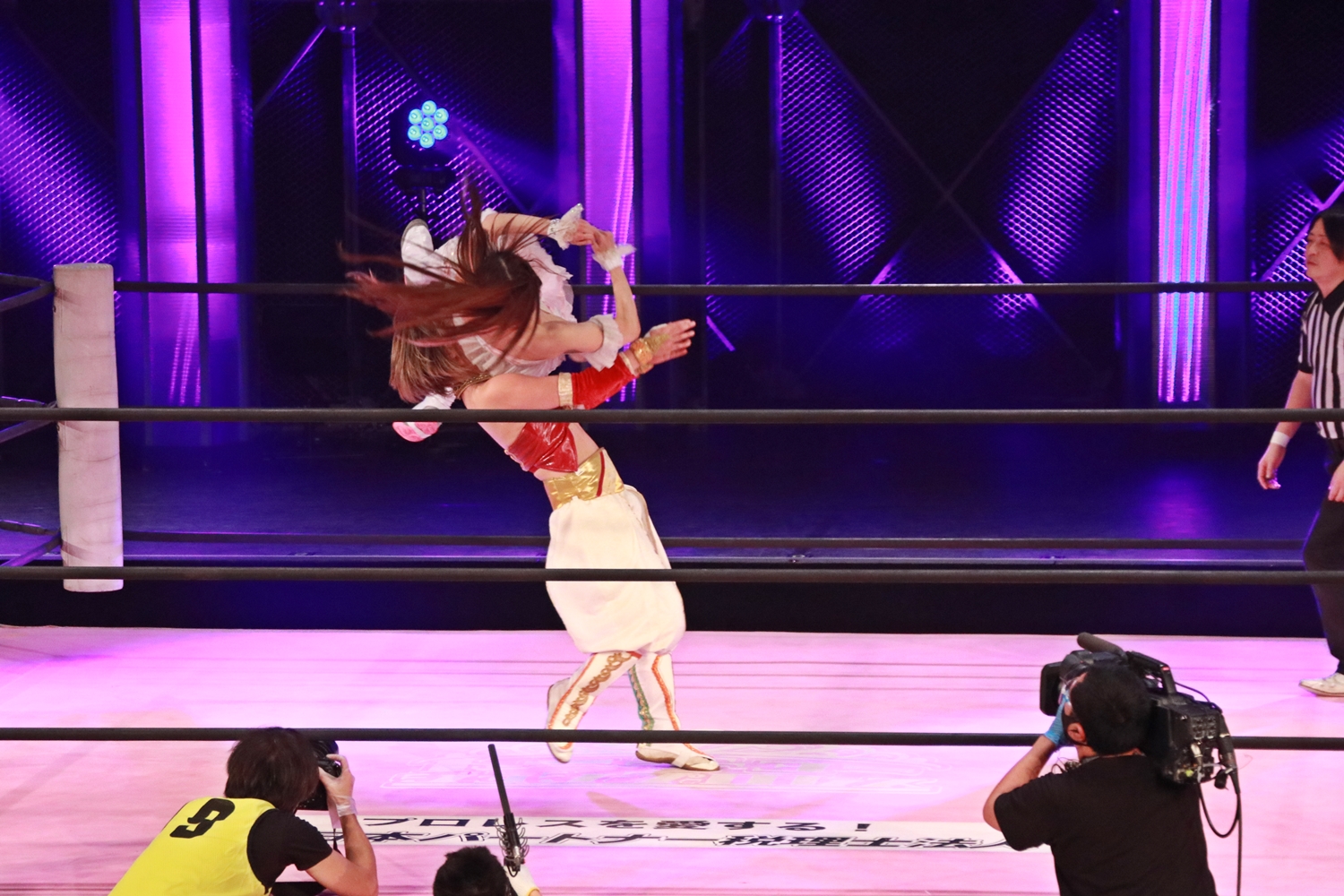

The reasons why this is easily one of my top five favourite matches of the year so far are fairly simple – these two know each other extremely well and have great in-ring chemistry, the match was Tokyo Joshi Pro’s biggest of the year and lived up to its billing, offering a level of drama that they save for the big occasions and a finish that felt genuinely unpredictable and exciting. This match’s significance as far as the highlights of 2020 go is pretty self-evident, in other words, but I could still pore over the details of this match – the little tricks and hooks and shifts it used to tell its story – for hours. From the ethereal music and sombre voice-over of the opening video package; to the shot of Mizuki covering her ears while I Can Fly played out over the Arena speakers because she needed to not be Yuka’s friend for the duration of this match; to the way the two worked around an obvious (and potentially disastrous) wardrobe malfunction without missing a beat and while still managing to produce matwork that was compelling and made sense; to that one spot where Mizuki bridged out of a pin attempt only to have her worked-over leg buckle and then be promptly and brutally dropkicked out from under her; to the final flurry of offence from Mizuki – Avalanche Cutie Special, Whirling Candy, Top Rope Diving Double Foot Stomp – which could have easily been a convincing finishing sequence, and which made the wild Magical Merry-Go-Round that Yuka hit in reply feel all the more impressive. The more I write, the more I feel I’m making the case that this was Mizuki’s spotlight, but the truth is a little different – this was the match that confirmed Yuka as a dominant champion on the level of Miyu’s peak, a near-indestructible unit whose eventual defeat now feels as weighty a matter for speculation as Miyu’s did. Whenever that defeat comes, it’s hard to imagine that the match in question could top this.

Suzu Suzuki vs. Masashi Takeda

8 November, Ice Ribbon, Ice Ribbon Dojo

Yes, you did read that correctly. Arguably the two most definitive aspects of Suzu’s identity as a wrestler are “developed extremely quickly” and “loves deathmatches”, and yet I really didn’t expect her to to be doing this kind of thing so soon, two weeks and a day after her appearance in Risa Sera’s Iron Woman match sort-of-maybe broke the seal on her deathmatch career. Of course, this match didn’t delve too deeply into Takeda’s bag of tricks, but Suzu’s at a point now where a little can go a long way – the Gran Maestro de Tequila onto a big pile of chairs was an especially memorable spot, since that move carries a load of history with it anyway, and it showcased an aptitude Suzu might well have going forward for finding creative ways to dump her opponents onto weapons. It wasn’t surprising that this didn’t turn into a full-blown deathmatch, but what was surprising was just how competitive it was – the finish still made it feel like a squash, but for most of its length this was a nicely-paced back-and-forth self-contained little smash of match, with Takeda reading the room and giving Suzu plenty of offence and shine without necessarily making it look as though he was holding back at all. There’s a long-standing Ice Ribbon tradition of this sort of match-up, but this iteration – which happened on the first part of a relatively obscure two-part PPV held in front of about 60 people – felt like it carried extra weight and meaning because of where Suzu is now and how she got into the business.

Pencil Army (Lulu Pencil & Emi Pencil) vs. Chris Brookes & Yuna Mizumori

11 November, Choco Pro, Ichigaya Chocolate Square

In recent chats with my High Speed Wrestling Podcast co-host Connor, there’s been some discussion around the idea that there really is no single trick in the wrestling book which is in and of itself bad – just degrees of execution which either make you feel something as a fan, or don’t. A while back, my own tastes and those of quite a few others were sharpened against the whetstone of the Johnny Gargano/Tommasso Ciampa feud, and its reception by wrestling fans online. While some praised what they saw as rich long-term storytelling, others, such as myself, saw only a feud which started off with some intrigue and drama before slumping into a mulch of over-baked narrative tropes, bad acting, self-regarding cinematography, and wrestling-as-medium having to contort itself awkwardly to accommodate these things.

In retrospect, I do regret some of the time and energy I invested in taking this storyline to task – clearly there were lots of people it did work for, and I simply wasn’t one of them; if there was a push from some fans to lionise the presentation of this feud as if it were some great work of narrative art, that disagreeable contingent didn’t really amount to much in the wider picture. Still, the Gargano/Ciampa episode had the effect of chilling a certain group of fans, myself included, on the idea of wrestling storytelling which seems to lean too heavily on what might be called “Sparknotes hooks” – Ciampa using a DIY t-shirt as a weapon in a heavy-handed metonym for his betrayal; Gargano losing the Last Man Standing match because he had simply become too violent, that kind of thing.

But yes. Nothing in wrestling storytelling is bad per se (at least nothing that isn’t racist, homophobic, etc, etc), and that includes Sparknotes storytelling. Wrestling isn’t prestige TV, but sometimes a wrestling program can pull together the hokey narrative elements that are this medium’s stock-in-trade in a way that adds up to more than the sum of its parts and produces something elevated enough to be justly compared, on its own terms, to Better Call Saul, or what have you. The feud to which this match was the blow-off, and which began back in September with a match I also had lots of praise for, is one such program. Based on how successfully this match managed to bring together more than a year’s-worth of storytelling, primarily around Lulu Pencil’s character but also taking in crucial beats in Emi Sakura’s and Yunamon’s 2020 arcs, I’d be very tempted to put it up there as the single best thing Choco Pro have done in their 9 months and 60-odd shows, and as one of the top five matches I’ll be revisiting come December to decide on my outright Match Of The Year.

I’ll refrain from saying too much about the match itself, partly because I could be here all day, partly because I’ve describe it at length in my Top 5 Matches of the Year post over at Substack, and partly because Stuart Iversen has done a brilliant job of distilling all of the key points into a review on his own site. Crucially, both Stuart and myself started crying at the exact same point: the moment where Lulu was offered the pink cap that Brookes won from her three months ago – her white whale, her raison d’etre – in return for saying “I quit” and thus conceding the match, and refused, triggering a dramatic change of heart on the part of Akki on commentary – in an instant, where he had previously been hoping out loud that Lulu would give up and live to fight another day, he now saw the fundamental importance of Lulu continuing to fight, and, forgetting himself, started shouting “STAND UP LULU! STAND UP LULU!”

The finish came a couple of minutes later, and was one of those moments where everything is suddenly illuminated – Lulu had reached an impasse where her body had nothing left to give but her mind was resolved to never, ever give up again; Emi’s small and necessary betrayal of Lulu in throwing in the towel to end the match mirrors the betrayal Brookes devilishly managed to draw out of Lulu in the tag match that preceded this, and these twin betrayals suggest that the Pencil Army has run its course; Brookes’ quiet and respectful exit following his team’s victory, handing Lulu her cap back as a just reward for her fighting spirit, signals that, at the same time, Lulu has outgrown her need for this unit – if the slogan of the Pencil Army is all about believing in yourself, then Lulu has just proven that this spirit is now fully internalised, and is able to stubbornly persevere even when her mentor’s will fails them. Lulu now feels a lot like Maki Itoh did throughout the whole two-year arc leading up to her title match against Miyu Yamashita at Korakuen Hall – somebody whose story is one of tiny personal victories carved out from the cliff face of constant inevitable defeat. It’s a story that hits a very tender part of my heart; it’s been about an hour since I watched this match now, and I still feel very soft.

Black Changita, Black R & BM vs. Aki Shizuku, Misa Kagura & rhythm

11 November, Just Tap Out, Korakuen Hall

New rookie klaxon! Suzu Suzuki’s brilliant singles match with Tomoka Inaba may have been the main story of this show from a joshi perspective, confirming Inaba’s slow-burn ascent to proper contender status, but at the other end of the card came something that’s always a big event for me – the debut of an eccentric newbie. It might be a while before Misa Kagura truly finds her feet in the ring, but from what I saw here – the completely over-the-top idol couture, the “Misa Special” signature submission – it very quickly became obvious that this is a journey I’m going to be following with interest.

Hiragi Kurumi, Satsuki Totoro, Ibuki Hoshi, Uno Matsuya & Tsukushi Haruka vs. Hikari Shimizu, Ami Miura, Mari, SAKI & Kakeru Sekiguchi

16 November, Ice Ribbon x ActWres girl’Z, Korakuen Hall

Maybe more than anything else on this entire Ice Ribbon x AWG show, the clash between Tsukushi and Kakeru which closed this team battle match felt like fantasy booking that had come out of my head and into the real world. The two are so well-matched in terms of style but have had very little opportunity to meet in-ring, so despite the fact that Ice Ribbon and AWG typically share lots of talent, it was nice to see that they could keep something in reserve for this crossover show. The stakes for this deciding clash were created by work done earlier in the contest though, first by Kurumi who tilted the odds massively in Ice Ribbon’s favour, eliminating Shimizu and Miura before then taking out both Mari and herself in a time-limit draw; and then by SAKI, who evened the score for AWG. There was a strong real sports feeling to the momentum swings here – I couldn’t help but thinking about the order in which each wrestler came into the match in terms of batting order in cricket, with SAKI in particular standing out as the no.4 who comes in after a top-order collapse and helps to steady the ship.

Suzu Suzuki vs. Tae Honma

16 November, Ice Ribbon x ActWres girl’Z, Korakuen Hall

While I clearly think Suzu deserves to be a major player in the conversation for 2020 Joshi MVP, there’s still an element of Suzu’s story that feels like it needs selling: there’s nothing natural about the idea of an 18 year old rookie becoming top company champion within two years of her debut after all, and even if Suzu has repeatedly proven her ability to hold her own in a big match environment, there’s still an ongoing need for a certain amount of additional work to be done in-ring – emphasising, reinforcing, highlighting; selling, basically – to put over her credibility as junior talent performing leagues above her expected level. Anyone reading this will know how much Suzu’s 2020 has meant to me, and will probably be aware of how much I enjoy Tae Honma; another factor that definitely played into my enjoyment of this match was the fact that I was able to watch it as-live and unspoiled, only a few hours after the fact. So too did the presentation of this show as a series of battles between two rival camps really help with the atmosphere here. But besides all this, it was the quality of selling that really blew me away – we know what a great actor Tae can be, but Suzu managed to bring her emoting game more or less to her opponent’s level here, and the screams that rang out through Korakuen Hall when Tae had her trapped in a potentially match-winning submission deep into the match were haunting and spoke of real jeopardy. Suzu did enough to convince me that Tae could win, and Tae did enough to convince me that Suzu was the rightful winner. I’m biased, but I can’t imagine too many wrestling fans, whether they’ve heard of Ice Ribbon or not, disagreeing with that verdict.

Hyper Misao vs. Super Sasadango Machine

20 November, Tokyo Joshi Pro, Shinjuku FACE

The week this match aired, I received a copy of the latest issue of Cabinet magazine, which features an essay I first started working on way back in 2017 about the nature of the relationship Roland Barthes had with pro wrestling. To crudely summarise the central point of the piece, there’s a strong similarity between the mindset which Barthes adopts as a critical method in his late work (specifically Camera Lucida), and a mindset typically inhabited by adult wrestling fans, regarding questions of truth. Drawing on a book written by performance studies scholar Sharon Mazer in the 1990s, I make the case that, once they are out of their “mark” phase, wrestling fans gravitate towards a kind of interaction with the medium that’s marked on the one hand by a desire to know more, and on the other hand by a desire to know less – to fail to grasp where the lines between the scripted and the spontaneous are drawn.

We’ll leave aside what all of this has to do with Barthes for the moment – the reason I bring this up here is because it struck me that this was exactly the reason why this hour-long segment, incorporating a Powerpoint presentation, a haiku competition, a “retirement” match which ultimately wasn’t, and an in-ring marriage proposal, ended up being such a successful bit of pro wrestling storytelling. A weird, free-wheeling, arguably self-indulgent bit of pro wrestling storytelling, but a success all the same. It all begins with Misao announcing, completely out of the blue, that this is going to be her retirement match; Dango, feeling unequal to the task of being Misao’s opponent for such an important match, decides instead to hold a competition modelled on The Bachelorette in which various members of the TJPW roster attempt to woo Misao into choosing them as her retirement opponent. Rika Tatsumi eventually wins, and the two have what is to all intents and purposes a retirement match, ending on an emotional note with a callback to the fist-bump spot that marked the moment when Rika “rescued” Misao from NEO Biishiki-gun last year.

Post-match, Misao speaks candidly to the crowd, describing the insecurities she felt as a TJPW member who started her career late and brought no previous experience in sports or idol culture to the table, outlining how she intended to go out on a high in 2020 before COVID interfered. What happened next was either wildly off-piste or so well-executed that it made marks out of all of us – Misao brings her boyfriend, DDT staffer Utashiro, to the ring and announces that whereas her original intention was to accept his earlier proposal of marriage once she had retired from wrestling, she now wants it all – Misao withdraws her retirement, and the two agree to get married, the rest of the TJPW roster squee-ing authentically though the whole bit.

Ultimately it doesn’t really matter where the truth ends and the fiction begins here, because this was through and through an expression of wrestling’s ability to hold kayfabe and reality in slippery, indeterminate suspension, and to make precisely that slipperiness into a core part of the spectacle. There’s something about the highly experimental way in which Super Sasadango Machine sees wrestling that breathes new life into this age-old gambit – I recall how the main event of the MUSCLE show at Sumo Hall last year walked an ever-shifting line between real and fake emotion, and Misao, as a devotee of Dango’s approach, had already given us something along these lines back in 2017 with her match against Jun Kasai. The moment where Utashiro whacked Dango over the head with a clipboard to stop him from interfering in the engagement, with Dango taking a big exaggerated bump to the canvas, felt like an extension of these matches as much as it felt like a real moment in the life of one Misao Kojima, 30, of Ibaraki Prefecture. This kind of post-truth has come in for a bad rap these past few years, but when pro wrestling really nails it there’s very little that can compare, to be honest.

Kakeru Sekiguchi & Miku Aono vs. Mii & Rina Amikura

24 November, ActWres girl’Z, Korakuen Hall

The main event here – a second run-out for the proven great match-up of LUMINOUS and SpiceAP – was a fitting one for the still-precious occasion of an ActWres girl’Z Korakuen Hall show, but the interest for this show was pretty evenly spread throughout the card. It doesn’t get said enough: there are massive, almost exponentially interest-building things that a tag tournament can do for you. It’s easy to forget that Magical Sugar Rabbits – a team big enough in TJPW lore that their own “Megapowers Explode” match could headline the company’s biggest show of 2020 – came out of a tournament where teams were thrown together by random lot. I expect that some of the teams that have come together for the purposes of this tournament will have a similarly long-term impact on the way the AWG roster stacks up going forward.

Pairing wrestlers up in fresh combinations is a great way to allow the individuals within the teams to sharpen and amplify their own identities, either in compliment or contrast to their partners. Elsewhere on this card, the team of Michiko Miyagi and Misa Matsui was a great example of the “contrast” model, and Sekiguchi and Aono in their own way have a pretty classic “red”/”blue” dynamic going on. But arguably the single standout team performance of this show came from Amikura and Mii, who were so obviously not winning here, but who treated the occasion as though they were fully convinced they might. Both wrestlers have been sitting pretty comfortably in a comedy/mid-card slot since their respective debuts, but this was a nice, intense, well-structured preview of what might happen if they’re given more matches with bigger stakes.

Risa Sera vs. Yuuki Mashiro

29 November, Ice Ribbon, SKIP City

It’s a crowded field, but purely in terms of concept this might be my favourite of Sera’s FantastICE defence matches – the idea that Yuuki Mashiro would win one (1) match via an over-the-top-rope-rules stipulation and become convinced that she’s now the master of that match type, enough to slow the roll of a champion who’s laid waste to all before her, is both entirely out of left field and extremely Yuuki Mashiro. The execution was every bit as good, with “Osaka Gacha King” Rina Yamashita at ringside to give Yuuki piggy-backs whenever she found herself in trouble, with Yuuki hurling abuse in Kansai dialect only to run (or be carried) away screaming whenever Risa came after her. It was a short affair which didn’t really go beyond the basic scenario conjured by its billing, but it didn’t need to – there couldn’t have been a more apt way for the most entertaining rookie of 2020 to receive the first title shot of her career.

December

Best Bros (Mei Suruga & Baliyan Akki) vs. RESET (Emi Sakura & Kaori Yoneyama)

5 December, Choco Pro, Ichigaya Chocolate Square

Unbridled levels of skill! This match reminded me of when I was told to watch a Yoneyama/Natsuki Taiyo match from the early days of STARDOM, with the promise that it represented the peak of the high-speed style I’d already developed a strong liking for in SEAdLINNNG. It delivered – I was blown away by the levels of finesse and invention there, and this match in its own way came close to that pinnacle, with both Mei and Akki raising their usual games for the special occasion of Emi Sakura’s One Big Match of the Season. Like the Mei vs. Mitsuru match from earlier in the year, it felt like all the competitors in this match were laser-focused on showcasing their aptitude for a certain style of wrestling, in this case a lucha-derived one of athleticism, spectacle and dazzle. Is there nothing they can’t do??!?

Aki Shizuku vs. Tomoka Inaba

6 December, Just Tap Out, Ice Ribbon Dojo

As mentioned above, Inaba now seems well and truly primed for a breakout year in 2021, not just because she’s improving with every performance, but also because, after a false start of sorts (Maika leaving for Stardom, rhythm being relegated back to trainee), there’s now an actual JTO women’s division forming around her feet, of which she’s clearly destined to become the top star. This losing effort against Shizuku – a 13-year vet who’s spent the last decade drifting between promotions such as Ice Ribbon, REINA and Marvelous, before finding her new calling as “Queen of JTO” this year – did very important work in laying the foundations for that climb, giving Inaba a nemesis to finally overturn when the time is right. Very simple stuff, but very promising for the year ahead.

Maika vs. Saya Iida vs. Saya Kamitani

20 December, STARDOM, Osaka EDION Arena 1

The Utami/Momo title match from the same show could very well have been my STARDOM Match of the Year, and the High Speed title match between AZM and Mei Hoshizuki would have to be a contender as well, but more than either of those matches, this Future of Stardomtitle contest convinced me that the beating heart of the company is the same as it ever was – it’s home-grown talent (or semi-home-grown, in the case of Maika) finding ways to make matches further down the card matter, defining their characters in relation to one another, building rivalries that can give the bookers something to fall back on for emotional heft when the inevitable churn of top-ranking talent happens, as it seems to happen every year. Iida was an immense presence here, and found a perfect foil in the brooding, undemonstrative Maika, while Kamitani injected pace and razzmatazz with her high-flying style. Watching along with friends, I commented in the chat that THIS is how you build sustainable interest in a promotion – by making sure the lower midcard is a place where the characters are big and the stakes feel high. It works for me at least – having given STARDOM the cold shoulder for most of 2020, I now feel inclined to keep in touch with their output, if only to see how Iida’s run with the title plays out.

Risa Sera vs. Akane Fujita

31 December, Ice Ribbon, Korakuen Hall

Ribbonmania was a show where nobody had their best match of the year – and was arguably better for it as a result. Everything felt concise and straight-to-the-point and the show ticked along at a consistently enjoyable rate; nothing fell into the memory-hole like a couple of matches at the Buntai did, victims to the life-changing spectacles either side of them.

Suzu’s title defence against Saori Anou felt like the first match of a potentially great feud, not the culmination of a year-long title arc, but it was exciting and did what it needed to do and it showcased some cool new offence from both wrestlers down the finishing stretch. The tag title match likewise did what it needed to do, providing a satisfying way for Maika Ozaki to finally recapture tag team gold at the third time of asking. The six-man featuring Nanae Takahashi’s first Ice Ribbon appearance in over four years was a fun knockabout spectacle which gave Ibuki Hoshi another chance to shine on the big stage, and bridged the less-serious and more-serious ends of the card effectively.

Nothing here stood outto the detriment of anything else, but there was a best match of the night, and it was the FantastICE title match between Sera and Fujita, a “Four Corners” Deathmatch where the corners in question contained cinder blocks, a metal baseball bat studded with tacks, a “mic board”, a box of lego, and Sera’s now-trademark light tube fan. The result was, as my friend George commented, “very unpleasant”, especially when the two took to whacking each other in the face with the spiked bat.

I’ve probably written enough this year about how accomplished Risa Sera is as a deathmatch wrestler now, but what felt notable about this match was how well paced it was – this didn’t exactly have the breakneck speed of that Isami Kodaka/Masashi Takeda match from a couple of years ago, but neither were there any moments where the match dragged as Sera and Fujita worked to get the next big spot ready. This was a procession of gruesome stunts, but it still felt very much like a competitive match, and by the time the final ridiculous stunt came – Sera diving knees-first into a prone Fujita, sandwiched between spikes and lego on one side and cinder blocks on the other – it felt like a logical escalation. A galaxy brain match in many ways, but Sera and Fujita have got so good at these by now that such thoughts barely enter into the equation, and plain old suspension of disbelief is enough to pull you through.